Born Clippy

Clippy was annoying, but at least it meant well. Today’s AI assistants—Clippy 2.25—are smarter but just as intrusive, and with murkier motives. If we didn’t like helpful interruptions then, why are we embracing them now?

Part 1 (of 4): Born to be bad?

By Darragh Coakley

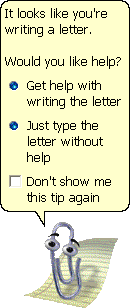

“It looks like you’re writing a letter” - Microsoft Office Assistant (Clippit/ Clippy)

I think at this stage it's better known only as a meme. But I'm old enough to remember Clippy IRL. Popping up to observe what I may be writing and to tell me how I should be doing it.

I feel a bit bad that I never took the help being offered. I doubt many did. But that's pretty much how Clippy's legacy has been enshrined. One of the great software design blunders of our times.

Benjamin Cassidy has a great breakdown of how Clippy came to be. And then not be.

It starts, as most things do, with good intentions. A genuine desire to design something to help people use computers at a time when only about 15% of houses had access to one. An alternative to gigantic printed manuals - then the only other form of tech support available. Based on (misunderstood) research from Stanford on social and emotional technological interfaces.

In the post-Theranos, post-WeWork, post-Metaverse landscape, Clippy's failings are surely minor. Insubstantial. And Clippy is now a staple of nerd culture, to Microsoft in-jokes to fan art to erotica fan fic (I’ll spare you a link to it). I genuinely find it comforting to view that as a kind of a happy ending for Clippy.

But regardless of the memes, Clippy is still utilised primarily as an example of what not to do in software design. How to design something that will turn people off a software they use or want or need.

Given all of the above, it's disconcerting that we are now entering the era of Clippy V2.25. The GenAI Clippy tsunami.

As identified in research such as that by Park (2022) and Casheekar et al (2024), we are now seeing more and more AI-powered helpers and support agents being embedded into all of the systems that we use.

We now see them, and look likely to continue to see them, inserted into all forms of softwares and services. They wear a different skin, but function the same

“I see you’re trying to do something. How about I get in the way of that?”

“I see you’re using this software to do 1 task. Did you know about this completely unrelated function?”

“I see you highlighted something. Do you want me to fill that with generative content?”

The fact that these new AI Clippys are broadly loathed seems to matter little. They are set to keep on coming. And unlike Clippy, it’s hard to assume that there are good intentions behind this. Beyond usability and issues of usability, function and design, Casheekar et al (2024) identify other major issues associated with these resources, including "hallucination, biases in training data, jailbreaks, and anonymous data collection".

In light of this deluge, Clippy serves as a useful indicator in this space, highlighting what can happen, what the legacy will be, when the software starts running the show.

Probably the biggest issue which Clippy faced was that it ultimately added little to what the user actually wanted to do. As noted by Kraus et al (2023), Clippy “did not act according to the user’s expectations and was perceived as distractive and not trustworthy”.

Schiaffino & Amandi (2004) present a useful 8-step process outlining the major issues that user interface agents have to achieve. From “Discovering the type of assistant each user wants” to “Providing the means to control and inspect agent behaviour”. Clippy was, in fairness, come and gone before the above even existed. But it’s worth nothing that Clippy did approximately none of these. It only ever offered intrusive feedback and input, unbidden.

Much of this was due to the fact that Clippy was optimised for first use. Its context - as outlined in Cassidy’s - was to help people who knew next to nothing about using a computer in a basic sense. Once you’d written a few letters, its presence added nothing. But that didn’t stop it from continually appearing and seeking responses.

Another part of the issue with the interactivity design of Clippy was the attempt to present affability and personalisation without the technical ability to do so. Clippy was cold, hard, unlearning, unchanging code but designed to create the illusion of an experience individualised to users.

As Nass & Yen (2010) noted “No matter how long users worked with Clippy, he never learned their names or preferences”. A similar, but broader, sentiment is echoed by Picard (2008), “While Clippyis a genius about Microsoft Office, he is an idiot about people”. None of us like to be plámásed, be it by computer or human.

Ultimately, Picard (2008) depicts what the actual experience of what the experience of engaging with Clippy might actually feel like IRL:

Someone whose name you don’t know enters your office. You are polite, but also slightly annoyed by the interruption, and your face is not welcoming. This individual doesn’t apologize; perhaps you express a little bit of annoyance. He doesn’t seem to notice. Then, he offers you advice that is useless. You express a little more annoyance. He doesn’t show any hint of noticing that you are annoyed. You try to communicate that his advice is not helpful right now, but he cheerily gives you more useless advice. Perhaps when he first came in you started off with a very subtle expression of negativity, but now (you can use your imagination given your personal style) let’s say, “the clarity of your emotional expression escalates.” Perhaps you express yourself verbally, or with a gesture. In any case, it doesn’t matter: he doesn’t get it. Finally, you have to tell him explicitly to go away, perhaps directly escorting him out. Fortunately he leaves, but first he winks and does a happy little dance.

Given the above, what other fate could poor Clippy have had but to be loathed?

References

Park, D. M., Jeong, S. S., & Seo, Y. S. (2022). Systematic review on chatbot techniques and applications. Journal of Information Processing Systems, 18(1), 26-47.

Casheekar, A., Lahiri, A., Rath, K., Prabhakar, K. S., & Srinivasan, K. (2024). A contemporary review on chatbots, AI-powered virtual conversational agents, ChatGPT: Applications, open challenges and future research directions. Computer Science Review, 52, 100632.

Kraus, M., Wagner, N., Riekenbrauck, R., & Minker, W. (2023, June). Improving proactive dialog agents using socially-aware reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM Conference on User Modeling, Adaptation and Personalization (pp. 146-155).

Schiaffino, S., & Amandi, A. (2004). User–interface agent interaction: personalization issues. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 60(1), 129-148.

Nass, C., & Yen, C. (2010). The man who lied to his laptop: What we can learn about ourselves from our machines. Penguin.

Picard, R. W. (2008). Toward machines with emotional intelligence. MIT Libraries

About the author

Darragh Coakley is a Technical Officer with the Department of Technology Enhanced Learning (TEL) at Munster Technological University (MTU), who has been working in the digital education and higher education space for over 17 years, across a range of roles, contexts and environments. He is an Advance HE Senior Fellow with a BA (Hons) in creative digital media, a MA in e-learning design and development, a level 8 certificate in designing innovative services, and a level 8 certificate in cyberpsychology.