Born Clippy

In part 3 of this series, we look perspectives learned from working in edtech towards the ongoing AI tsunami and why both the minute specifics and the broader context are important - despite attempts to often obfuscate both. Final part coming soon

Part 3 (of 4): edTech

By Darragh Coakley

“Men have become the tools of their tools” – Henry David Thoreau

So Clippy is returning. But for less than honourable reasons.

For those of us working in edtech, I think there has always been an assumption that we all can't wait for AI.

That we - because we work in ed-TECH - will inevitably be the chosen evangelists for it.

That assumption is often based on a fundamental misunderstanding of the gig.

This is reflected in many of the models and frameworks which those of us in edtech rely upon.

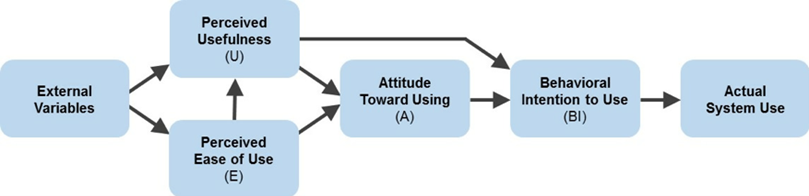

The Technology Acceptance (TAM) Model (Davis, 1989), the Passive, Interactive, Creative, Receptive, Active, Transformative (PIC-RAT) Model (Kimmons et al, 2023), and the Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TEPACK) Model (Mishra, 2019) among others.

Nobody would claim that these models are edtech stone tablets carried down from Mount Sinai.

There are issues, assumptions and correlations with all of the above. But it is worth noting that the elements the models are composed of are less to do with the specifics of technology or technological features. And far far more to do with the human relationship to and use of the technology.

Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, attitude toward using, behavioral intention to use, student's relationship to tech, teachers' use of tech in practice, content knowledge, pedagogical knowledge, etc.

I’ve found it’s useful to have a framing device of an actual sector for looking at these kinds of questions.

So will AI replace doctors? There have no doubt been situations where genAI has helped to point to an accurate diagnosis, or led to some breakthrough. And it is important not to dismiss the reality of these cases and the impact it has had on patients and their families.

But it is also important to look with clear eyes at the grounded reality, identify where the AI fits, and the purpose it serves, within the broader context.

Speaking to the case linked above of tethered cord syndrome, Kostick-Quenet (2025) articulates how AI can be beneficial to clinicians, noting that “A primary utility of AI in healthcare is to identify patterns that are difficult for clinicians to see on their own (e.g., due to human imperceptibility, insufficient resolution, voluminous data)”. That same paper goes on to note however that “they rarely point to a single truth and more often present a range of probabilities. As such, AI systems designed to augment clinical decision making face the same problems of acceptability and uptake as consumer-grade AI-powered chatbots and answer engines.”

More direct AI engagement does appear to be happening in some spaces. Kumar et al (203) have looked at the use of AI algorithms for analysing things like X-rays and CT scans for patterns and/ or indicators of disease. Manco et al (2021) points to the potential of similar analysis and pattern recognition to forecast future health outcomes. But all these processes take place within a context of ultimately supplementing and informing human decision-making. Rather than replacing it.

So much like any other use of the tech, it works to help supplement tasks but would not work serving a function that requires any kind of autonomous activity.

If all of this sounds self-evident, it’s cause it is.

As mentioned in the last in this series, a specific tool provides a specific solution for a specific need within a specific context. I think that is how most of us use any genAI tool in reality.

But even as someone who has done some reading and has a bit of critical analysis of the tools, I find myself it can be hard not to get sucked into the spin being told about AI from our silicon valley overlords.

This is not by accident.

They will espouse the purpose of AI as a tool to offload laborious work, boost productivity, and leave more time for human creativity and ingenuity. And simultaneously they will try to sell management on the notion that you can replace flesh and blood people (more specifically the need to pay them) with whatever they’re selling.

One of their biggest sticks for beating down dissenters on this is the promised further evolution of AI (“Well it’s not doing it right now, but it’s evolving so rapidly it’ll be doing it soon”). And certainly nobody can deny that the timeline of evolution of AI has been dramatic the last few years. But this evolution is confined within the specific functionality of the technology. Not within the wider, real-life world.

As impressive as the evolution of e.g. ChatGPT is, there’s no roadmap or explainer for how it can replace people in the service of people in the real world. And however much it evolves in its perceived and presented “intelligence”, this does not overcome this issue.

A big part of the edtech gig is - or at least should be - gatekeeping.

Ensuring that only technology which serves a clear educational purpose is engaged. I thought that at this point we had all internalised that as a given. But the current AI blitzkrieg has taught me otherwise.

Beyond critical analysis, I’d go farther and argue that, when dealing with tech, a little (or even a hefty dose of) cynicism can be useful. Not least when considering who is selling to you.

I don’t think it is effective or appropriate to compare AI to things like theranos or the metaverse. But it is worth remembering that the latter was at one point being heralded as transformative technology which would upend everything.

I don’t think that claim has a leg to stand on no more.

We can often fall into a habit of talking about tech absent of any kind of context. But it never is.

The broader point is to beware Greeks bearing gifts. And tech bros telling you how their new tech is inevitable and transformative and you don’t need anything or anyone else.

There’s probably something sus about that horse.

Baxter Dury - I'm Not Your Dog (Official Music Video)

References

Davis, F. D. (1989). Technology acceptance model: TAM. Al-Suqri, MN, Al-Aufi, AS: Information Seeking Behavior and Technology Adoption, 205(219), 5.

Kimmons, R., Draper, D. E., & Backman, J. (2023). The PICRAT Technology Integration Model.

Mishra, P. (2019). Considering contextual knowledge: The TPACK diagram gets an upgrade. Journal of digital learning in teacher education, 35(2), 76-78.

Kostick-Quenet, K. M. (2025). A caution against customized AI in healthcare. npj Digital Medicine, 8(1), 13.

Kumar, Y., Koul, A., Singla, R., & Ijaz, M. F. (2023). Artificial intelligence in disease diagnosis: a systematic literature review, synthesizing framework and future research agenda. Journal of ambient intelligence and humanized computing, 14(7), 8459-8486.

Manco, L., Maffei, N., Strolin, S., Vichi, S., Bottazzi, L., & Strigari, L. (2021). Basic of machine learning and deep learning in imaging for medical physicists. Physica Medica, 83, 194-205.

About the author

Darragh Coakley is a Technical Officer with the Department of Technology Enhanced Learning (TEL) at Munster Technological University (MTU), who has been working in the digital education and higher education space for over 17 years, across a range of roles, contexts and environments. He is an Advance HE Senior Fellow with a BA (Hons) in creative digital media, a MA in e-learning design and development, a level 8 certificate in designing innovative services, and a level 8 certificate in cyberpsychology.